Crossing the Barranca, 1930 by Diego Rivera

In September 1929, Diego Rivera accepted a commission from Dwight Morrow, the ambassador of the United States to Mexico. Morrow offered to pay from his own pocket for a Rivera mural to be painted in the former Cuernavaca palace of Hernan Cortes, the conqueror of Mexico. Morrow had been a partner with J. P Morgan, who the year before was so brutally caricatured by Rivera. Morrow had been dispatched to Mexico in 1927 by Calvin Coolidge and performed brilliantly. He was everything an ambassador should be and so often isn't: intelligent, moderate, respectful of differences in culture and politics, well-mannered, outgoing, and willing to compromise to avoid stupid conflicts. He established a personal friendship with Calles, convinced the strongman to ease up on the war against the Catholic church, and persuaded American celebrities to visit Mexico in the spirit of goodwill.

At that time, Rivera had a practical consideration: he needed money. After marrying Frida Kahlo, he had promised to pay the balance of the mortgage on the Blue House, which his father-in-law was about to lose. Morrow's offer was for $12,000, a huge sum in those days. From that fee, Rivera would have to pay his assistants and buy materials; it was still a good deal. He agreed.

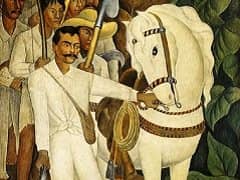

I chose to do scenes from the history of the region in sixteen consecutive panels, beginning with the Spanish conquest. The episodes included the seizure of Cuernavaca by the Spaniards, the building of the palace by the conqueror, and the establishment of the sugar refineries. The concluding episode was the peasant revolt led by Zapata. In the panels depicting the horrors of the Spanish conquest, I portrayed the inhuman model of the old, dictatorial Church. I took care to authenticate every detail by exact research, because I wanted to leave no opening for anyone to try to discredit the murals as a whole by the charge that any detail was a fabrication. In some of the panels my hero was a priest, the brave and incorruptible Miguel Hidalgo, who had not hesitated to defy the Church in his loyalty to the people and to truth."

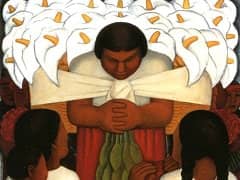

Rivera left for Cuernavaca, starting work in January 1930. He labored within walking distance of the extravagant weekend mansions of the corrupt generals and cronies of Calles, clustered together around the mansion of the Jefe Maximo on what Mexicans called "The Street of the Forty Thieves." The frescoes were painted on three walls of the outer colonnade, facing the Valley of Mexico and the great volcanoes called Popocatepetl and Iztacciihuatl. Once again, Rivera was forced to consider the effects of light and weather. He added some painted grisaille bas-reliefs beneath the main panels, to serve as a kind of visual counterpoint. In all these panels, Rivera brought forth what was becoming his stock company of exploiters, exploited, and saviors, and once again, the Indian girl with the pigtails. But he surrendered the clenched and meticulous rendering of his painted surfaces and breathed some new life into the subject matter. The panel called Crossing the Barranca, on the west wall, is handsomely composed and painted, depicting the conquistadors driving Indians and campesinos (in a deliberate anachronism) across a deep gully, all engulfed by timeless tropical foliage.